Baltic Seabird Project

Seabirds are near the top of their food web, and changes in their habitat are reflected in their behaviour. Climate change, overfishing, eutrophication and toxic emissions are all examples of human impact on the environment that can negatively affect the life of Baltic birds in different ways. By studying changes in the birds’ behaviour, we can get an idea of what is occurring beneath the water’s surface. Much like the canary in the mine, the seabirds act as “messengers” of environmental change and overall health. When combined with other research projects, seabird research can provide greater insight into the Baltic Sea ecosystem, and thereby inform decisions regarding best environmental management practices.

With this in mind, Olof Olsson and Kjell Larsson initiated the research project “Seabirds in the Baltic Sea” in 1997. The project had two focal species, the Long-tailed Duck (Clangula hyemalis) and the Common Guillemot (Uria aalge, also known as Common Murre). Eventually, the project divided into two parallel projects, in which Olof focused on guillemots, and Kjell on long-tailed ducks. From the start, their fieldwork studies were funded by WWF Sweden.

For almost 20 years now, guillemot research has continued under the leadership of Olof and his colleagues, among them Henrik Österblom and Jonas Hentati-Sundberg. Although the project has changed and evolved in scope and focus over time, the starting point has always been the unique conditions presented by the seabird colonies on Stora Karlsö. In addition to research on Common Guillemots, the project has worked with Razorbills (Alca torda), Lesser Black-backed Gulls (Larus fuscus), European Herring Gulls (Larus argentatus), and Great Cormorants (Phalacrocorax carbo), as well as conducting pilot studies on Arctic Terns (Sterna paradisaea) and Common House Martins (Delichon urbicum). Guillemots, however, have always been the focal study species, as represented by the construction of the “Auk Lab,” a manmade nesting research platform unique in the world, and what is likely the largest annual ringing effort of guillemot chicks worldwide. What began as just one part of the project “Seabirds in the Baltic Sea” has today become an ambitious, long-term research project with employees and partners across the Baltic and beyond.

The Baltic Sea – an ecosystem in transition

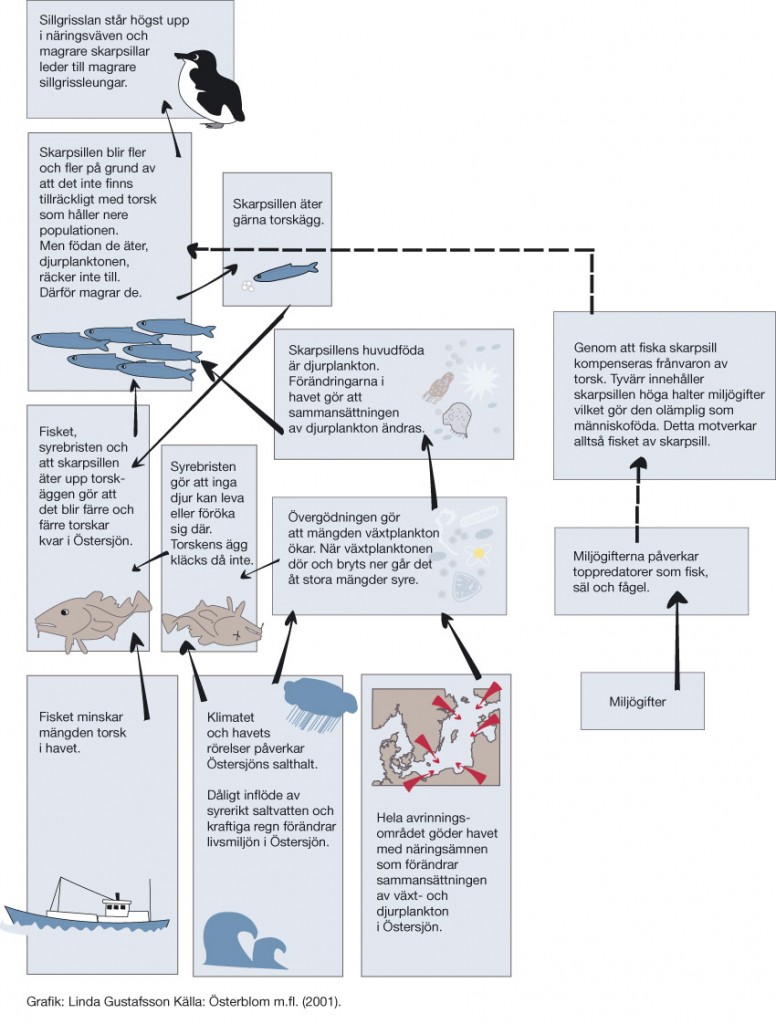

Our research has shown that the Baltic Sea ecosystem is in a transition period. Since the 1970s, Common Guillemot chicks have been weighed at the time of ringing, and up until the late 1980s, average chick weight had remained stable. However, following that time and up until 2000, a gradual decrease in chick weight was observed each year – despite the fact that the guillemots’ main food source, sprat (Sprattus sprattus), showed marked population increases during the same period. But how could this be? Sprat in turn eat zooplankton, and during the years of strong sprat population growth, zooplankton became scarce. Consequently, individual sprat were on average smaller in size, despite larger overall population numbers. Previously, sprat populations had been limited by cod predation, the populations of which were decimated by overfishing in the late 1980s, thus allowing sprat populations to grow unchecked.

After 2000, sprat populations were again reduced while the average nutritional value of each individual increased. As expected, the average weight of guillemot chicks subsequently increased. The observed relationship between guillemot chick weight and sprat condition is one example of how seabird research can help track changes in the Baltic Sea ecosystem.

Illustration of part of the ecosystem that surrounds Common Guillemots on Stora Karlsö © BSP / Linda Gustafsson

Research provides environmental initiatives

Research results produced by the Baltic Seabird Project have attracted frequent attention from the media and policy makers alike, leading to positive changes in environmental policies and awareness. For example, the decision to establish the State Marine Environment Commission (Havsmiljökommission) was influenced in part by research results published on ecosystem changes. Additionally, restrictions on the use of drift nets in commercial fishing were implemented following research published exposing the number of seabirds caught as by-catch.

Field station at Stora Karlsö

A remarkable site

If you are interested in studying the Baltic’s seabirds and marine ecology, you will be hard pressed to find a better place to do so than on Stora Karlsö. Situated six kilometres off the west coast of Gotland and at the same latitude as the northern tip of Öland, Stora Karlsö is home to the Baltic Sea’s largest auk colony, as well as nationally important breeding populations of Lesser Black-backed Gull, Velvet Scoter, and Common Eider. The Common Guillemot colony on Stora Karlsö, which consists of approximately 14 000 breeding pairs (or approximately 35 000 to 45 000 individuals), offers a unique study opportunity when compared to many other colonies within the species’ range. The majority of the worlds’ Common Guillemots nest on inaccessible cliffs rising out of the North Atlantic, occasionally to heights reaching hundreds of meters tall. On Stora Karlsö, however, we are rarely more than a few dozen meters from the birds, occasionally a mere 3-4 meters, and, with the help of the Auk Lab, a few scant centimetres! Aside from guillemots, a number of other seabird species can be found on the island, including Razorbills, Lesser Black-backed Gulls, Herring Gulls, Arctic Terns and Great Cormorants, and many others that can be studied and used for comparisons or to add new insights to our understanding of the Baltic Sea ecosystem.

Historic Land

Stora Karlsö has long been a site for bird research, with the first guillemots ringed in 1913. This is among the earliest ringing efforts recorded in Sweden, and the beginning of what is likely the longest continued ringing effort anywhere in the world. The exciting history of the island, however, stretches back far longer than just the last hundred or so years. Excavated in the 1880s, the cave Stora Förvar was one of Sweden’s first systematic archaeological excavations. Nearly 4.5 meters of earth were dug out, representing a number of cultural layers and containing artefacts from some of Gotland’s earliest settlers in ancient times. The island was used for thousands of years thereafter: for fishing and seal hunting in the Stone Age; for trading in the Viking Age; and as a naval port for the Danish navy in the 1500s, to name just a few. In the 1800s, the spread of the Romantic interest in nationalism and nature among wealthy citizens led to the establishment of a stock company, Karlsö Hunting and Animal Welfare Society, in the 1880s. Originally, the company most closely resembled a socialite club, but over time became increasingly similar to a non-profit association for nature conservation. Although the company, which became popularly known as the “Karlsö Club,” was hunting-oriented from the start, it was principally the protection of nature that formed its initial foundation. In fact, the club’s work led to Stora Karlsö becoming one of the world’s first protected nature reserves. The Karlsö Club continues to be a driving force of nature conservation on the island today, in addition to ensuring that the island remains accessible to the general public. Both scientific and cultural research proposals to work on the island are welcomed, providing a positive and productive research environment. Since its inception in 1997, the Baltic Seabird Project has had excellent relations with the Karlsö Club.

Field station

As researchers, a large part of our time on Stora Karlsö is spent in the field, although we also rent office space, storage space, and some of the island’s hostels for work and accommodation during the field season, which runs from early May to mid-July. On the island, we have our own little house with a dozen beds and a kitchen. The community and cooperation with the island’s supervisor, guides, and accommodation and restaurant staff are an important and positive part of our time in the field.

For more information on Stora Karlsö, visit Karlsö Club’s website here: Stora Karlsö

Sponsors and partners

Karlsö Hunting and Animal Welfare Society – “Karlsö Club”, and the Palmska Foundation

The Karlsö Club owns and manages the island of Stora Karlsö, in addition to managing the island’s tourist business. All practical elements associated with the BSP’s fielwork is done in close cooperation with the Karlsö Club.

The board of the Karlsö Club manage the Palmska Foundation, allocating money for research and research related activities connected to Stora Karlsö island.

WWF Sweden

The WWF has been one of the BSP’s main funders since the project’s start in 1997. The WWF and the BSP work together to disseminate research results and knowledge of the Baltic Sea ecosystem to politicians and decision-makers. Seabird research on Stora Karlsö is an important part of the WWF’s international Baltic Sea Region Programme.

WWF Sverige (in Swedish)

Milkywire

VOTO

Formas

Scientific Publications

Due to copyright reasons we cannot offer all of our publications for direct download, although some have links to where they may be downloaded. If you are interested in obtaining access to any of our publications, however, you are welcome to contact us.

Contact

Jonas Hentati-Sundberg, Research director

073 – 938 79 69

Aron Hejdström, Project coordinator

073 – 630 83 92

Mailing address

Baltic Seabird Project Association

c/o

Aron Hejdström

Sanda Västerby 568

623 79 Klintehamn

SWEDEN

Baltic Seabird Project Association

Org. nr: 802535-1571

Photos on the webbpage: © BSP/Aron Hejdström